Colour me bad: Researchers in Australia develop colourimetric sensors for packaging to reduce food waste

It is based on the colourimetric polymer sensor technology, which changes colour when it reacts with compounds produced during food spoilage.

Typically, the sensor is blue, which indicates the food or drink is fresh. When it turns purple, it means the food should be consumed soon, and when it turns red, it means the food has already gone bad.

Associate Professor Rona Chandrawati from the School of Chemical Engineering at UNSW Sydney, said the team has been working on this technology for five years, and hopes to eventually commercialise it.

“We envision having these colourimetric sensors attached to food packaging in our fridges so we can contribute to reducing food waste and also help eliminate the confusion on the date marking tools that we currently have.”

Solution to food waste

Chandrawati told FoodNavigator-Asia the team was interested in finding a solution to the global food waste problem.

According to the UN FAO, about one-third of food is wasted along the supply chain: “That's quite a significant amount of food. Furthermore, at the consumer level, there are sometimes confusion and a misunderstanding of the different best-before, use-by and expiry dates.

“For example, consumers will throw food before, close or after the best-before date. On the other hand, when food is not stored properly, the best-before dates are not a good indicator because these dates are static, they do not adapt to variable conditions.

“We realised how much food we have wasted, and on the other side, there are certain regions or countries that do not have enough food for consumption.”

Technology

In this video, Chandrawati explains how the technology works.

The team has created a sensor to test for lactic acid in milk. When milk is contaminated with bacteria or spoiled, it has a higher level of lactic acid.

“We design polymers that have chemical groups that will react specifically to changes in food composition (for example, the lactic acid level), and once that reaction occurs, it will change the conjugated backbone of these polymers, changing how it absorbs light. Visually, we will be able to see the colour change.”

It has also created a sensor for meat. When meat goes bad, spoilage bacteria produce volatile organic compounds or gases such as ammonia. The sensor will react with the specific compound and changes colour accordingly.

They have also tested sensors on fruits, reacting with ethylene gas produced during ripening.

While colourimetric sensors are not new, Chandrawati said that working with polymer materials would allow more flexibility compared to chemical dyes, that are most frequently used as present, usually to gauge optimal temperatures for food products.

Work in progress

However, this research is still a work in progress: “There are many challenges ahead, we have to make sure we optimise them before commercialisation,” she said.

“Sometimes the same products have different constitution which will lead to different level of the compounds produced during spoilage. We need to ensure these sensors are carefully designed to detect compounds within the relevant range and do not overestimate or underestimate the spoilage.”

While the sensors are currently designed to attach to primary packaging at the moment, Chandrawati said they could also be designed for use at the producer or distributor level.

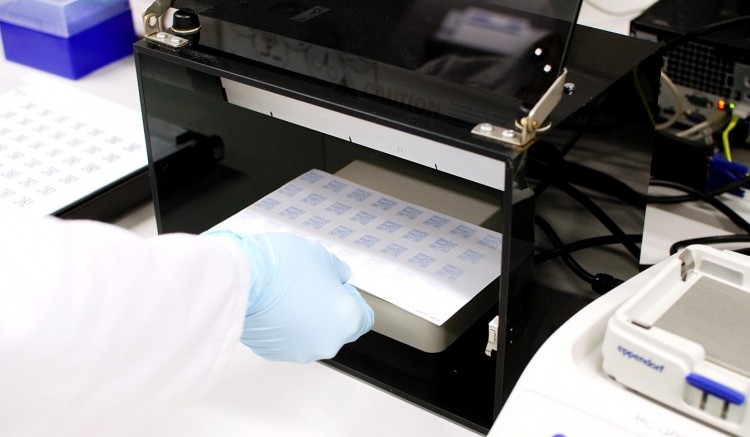

The team is also working on developing the colourimetric sensors in QR code format: “Imagine a QR code that turns from blue to red to indicate users there is contamination or spoilage.”

Dr Rona Chandrawati has been named a finalist of the 2021 Australian Museum Eureka Prizes, Australia's most high-profile science awards.